What is Art Therapy?

Art therapy is a relatively new field rooted in the idea that creative expression can help to foster healing and improve mental well-being. According to the American Art Therapy Association, art therapy uses “active art-making, creative process, applied psychological theory, and human experience within a psychotherapeutic relationship.”1 When done consistently and facilitated by a professional art therapist, art therapy can be used to “improve cognitive and sensory-motor functions, foster self-esteem and self-awareness, cultivate emotional resilience, promote insight, enhance social skills, reduce and resolve conflicts and distress, and advance societal and ecological change.”1

In practice, art therapy may consist of creating artwork utilizing a variety of mediums: collage, drawing, painting, sculpture, etc., or any combination thereof. It also may incorporate various talk therapy techniques. As clients create art, they may analyze what they’ve made and how it makes them feel. This can aid the therapist in better understanding a client’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviors.

History and Prominent Figures

Although art has been utilized as a means of communication, self-expression, and conflict resolution for thousands of years, the establishment of art therapy as a specific therapeutic approach only took place recently, in the mid-20th century.

Margaret Naumburg, commonly described as the “mother of art therapy,” established the Walden School in her home city of New York in 1915.2 She believed that children who could express themselves creatively would experience healthier development. She viewed the creative process as a methodology similar to verbal expression, meaning that it allows the unearthing of unconscious thoughts and emotions. Once the symbolic expression was combined with cognitive and verbal aspects of experience, healing could take place. Naumburg began publishing clinical cases in the 1940s, referring to her work as “dynamically oriented art therapy,” and was the first to define it as a distinct profession. British artist Adrian Hill also coined the term “art therapy” around the same time as Naumburg, in 1942, after discovering the benefits of drawing and painting while recovering from tuberculosis.2 Naumburg was the first to receive the highest award in art therapy, the Honorary Life Member from the American Art Therapy Association, in 1970.

Another influential figure was Edith Kramer, a painter that fled Hitler’s Germany for 1938 for New York City.2 While conducting art classes in Prague for refugee children, she recognized that art could help alleviate trauma. She published Art Therapy in a Children’s Community in 1958, which described the importance of how it is the creative process and products themselves that are healing. Whereas Naumburg employed verbal inquiry in order to further the client’s exploration of the unconscious mind, Kramer relied very little on talking, if it was used at all.

How it works

Art therapy works by emphasizing a mind-body connection. The process of art-making may enable clients to get in touch with feelings that are difficult to express in words. Additionally, the process of creating art has been shown to reduce the level of cortisol, the hormone associated with stress3.

Art therapy can provide an outlet for intense, destructive, and shameful emotions while supported by an adult figure and without fear of judgment. In fact, it has been found to be beneficial for children with behavioral issues for this reason. “Art can act as a ‘container’ for powerful emotions,” providing a purposeful target to outwardly direct these emotions instead of bottling them up or expressing them in harmful ways.9

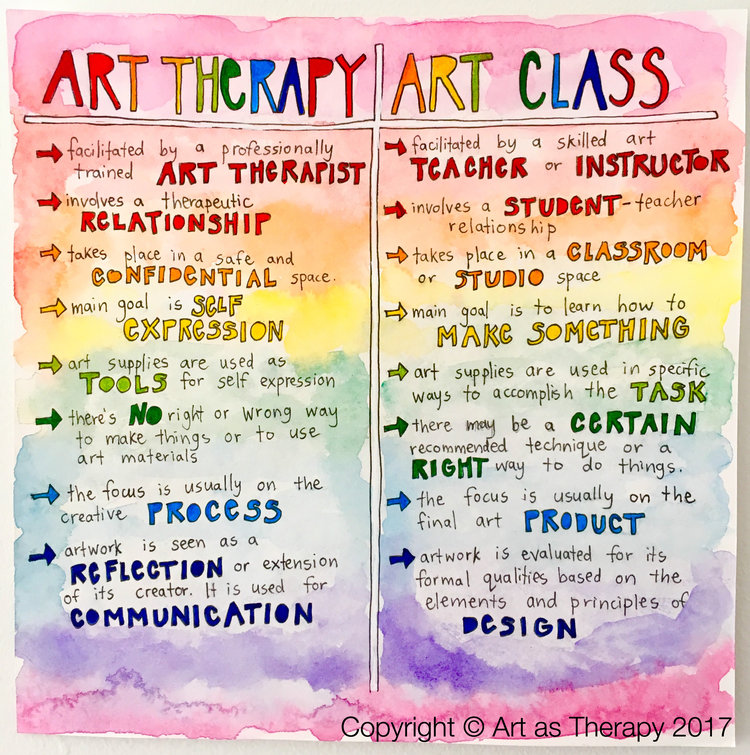

Art therapy isn’t the same as an art class, and you don’t need to be an artist to participate and benefit. It doesn’t matter how “good” the final product looks, and art therapists aren’t focused on technique or creating a specific finished product. Rather, it’s all about the process and self-expression involved in the creation of the work. It’s also not just for children. Art therapy techniques can be therapeutic for ages all across the lifespan. Through creating art, clients can focus on their own perceptions, feelings, and experiences. When something is created, it then becomes external to the individual, making the thoughts and feelings separate and something that can be controlled.

Art Therapy Resources

- https://arttherapyresources.com.au/

- https://positivepsychology.com/art-therapy/

- https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/arts-and-health/201002/the-ten-coolest-art-therapy-interventions

- https://arttherapy.org/

Works Cited

- American Art Therapy Association. Retrieved July 18, 2022, from https://arttherapy.org/

- Junge, M.B. (2015). History of Art Therapy. In D.E. Gussak and M.L. Rosal (Eds.), The Wiley Handbook of Art Therapy (1st ed., pp. 7-16). John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118306543.ch1

- Kaimal, G., Ray, K., & Muniz, J.(2016). Reduction of Cortisol Levels and Participants’ Responses Following Art Making. Art Therapy, 33(2), 74-80. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2016.1166832

- Levels of cortisol, a hormone associated with stress, were lowered after art making for approximately 75% of the sample.

- Lusebrink, V. B. (2011). Art Therapy and the Brain: An Attempt to Understand the Underlying Processes of Art Expression in Therapy. Art Therapy, 21(3), 125-135. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2004.10129496

- Mind-body interaction

- Regev, D. & Cohen-Yatziv, L. (2018). Effectiveness of Art Therapy With Adult Clients in 2018—What Progress Has Been Made? Frontiers in Psychology, 9(1531). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01531

- Schouten, K. A., de Niet, G. J., Knipscheer, J. W., Kleber, R. J., & Hutschemaekers, G. J. M. (2015). The Effectiveness of Art Therapy in the Treatment of Traumatized Adults: A Systematic Review on Art Therapy and Trauma. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 16(2), 220–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838014555032

- Slayton SC, D’Archer J, Kaplan F. (2011). Outcome studies on the efficacy of art therapy: a review of findings. Art Therapy, 27(3), 108-118. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2010.10129660

- Waller, D. (2006). Art Therapy for Children: How It Leads to Change. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 11(2), 271–282. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104506061419