LGBT Pride Month

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, the word “pride” is defined as the quality or state of being proud: such as, a reasonable or justifiable self-respect; delight or elation arising from some act, possession, or relationship.11 Pride, as opposed to shame, rejects any feelings of guilt, inadequacy, or censure.12 Considering the lengthy history involved in fighting for LGBT acceptance and legal rights, the concept of pride is powerful, and even revolutionary – especially in the context of mental health.

LGB adults are more than twice as likely as heterosexual adults to experience a mental health condition,17 and transgender individuals are nearly four times as likely.20 Additionally, as many as 1 in 5 LGB adults have attempted suicide during their lifetimes9; in transgender and gender non-conforming individuals, the rate has been found to range between 32% and 41%.3, 6

It’s no surprise that bullying and other forms of harassment negatively affect one’s mental health. Self-acceptance is crucial to mental wellbeing,10 especially when the world is telling you that who you are is wrong. Cultivating understanding and respect is integral to creating a more empathetic society and a better world – listening to others’ stories and learning about their collective history is just the first step.

LGBT activism originated much earlier than people think. American homophile organizations such as the Daughters of Bilitis and the Mattachine Society coordinated some of the earliest demonstrations of the modern LGBT rights movement, beginning with their founding in 1950 and 1955, respectively.1 Although Illinois was the first state to decriminalize homosexuality in 1962 by repealing their sodomy laws, it wasn’t until 2003 that laws against sodomy were declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court, making homosexuality decriminalized nationwide.1 Additionally, homosexuality was classified as a psychiatric disorder until 1973.1 Same-sex marriage was not legalized nationally in the United States until 2015.1

In the 1960s, it was the norm for gay bars to be run by the mafia, as such establishments provided ample opportunity to pay off wayward police officers.16, 18 Previously, the New York State Liquor Authority did not give out licenses to establishments that served gay patrons. Kissing, dancing, or trying to find someone of the same sex to take home for the night were all considered “disorderly conduct,” and could result in bars losing their liquor licenses.16 To get around these restrictions, many gay bars operated as self-proclaimed “bottle bars”, or private clubs where members would bring their own alcohol; however, the mob would still provide liquor, just more secretively.7, 16, 18 Despite being paid off, however, police frequently raided gay bars to arrest patrons without identification.7, 18 Additionally, men were often hauled in for dressing in drag, and women were, too, if they weren’t wearing at least three pieces of traditionally feminine clothing.7 Sometimes cops even went to extreme measures, sending female officers into the bathroom to verify patrons’ sex.7

Beginning in 1965, activists in Philadelphia staged annual pickets outside Independence Hall on July 4th, as an “Annual Reminder” that gays and lesbians were being denied basic civil rights protections.15, 19 However, these protests were much more reserved than what we typically see today. According to gay activist Fred Sargeant, “The walk would occur in silence. Required dress on men was jackets and ties; for women, only dresses. We were supposed to be unthreatening.”15 The goal of these pickets was to demonstrate that gays and lesbians were normal, everyday people, capable of holding down a job and appearing respectable. By appealing to societal standards, they hoped to convince the public that they were worthy of positive, or at least neutral, regard.

One of the most recognized turning points in gay activism occurred when, in the early morning of Saturday, June 28th, 1969, a police raid took place at the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar at 53 Christopher Street in Greenwich Village, Manhattan, New York City.2, 8, 18 Police had already raided the bar that Tuesday, and this time they were hoping to shut it down for good.18 Although raids were a common occurrence, this time things didn’t go as planned. A scuffle broke out when a woman in handcuffs, recalled by bystanders as biracial lesbian Stormé DeLarverie,14 was escorted from the door of the bar to the waiting police wagon several times. She escaped repeatedly and fought with four of the police, swearing and shouting, for about 10 minutes. DeLarverie sparked the crowd to fight when she looked at bystanders and yelled, “Why don’t you guys do something?”14 The moment an officer picked her up and heaved her into the back of the wagon, the crowd erupted. Eventually, police were forced to barricade themselves in the bar to await backup.8, 19

In an article published in the Voice, witness to the June 28th police raid Morty Manford shared that the uprising was “a slight lancing of the festering wound of anger at this kind of unfair harassment and prejudice. We had just been kicked and punched around symbolically by the police. They weren’t doing this at heterosexual bars. And it’s not my fault that the local bar is run by organized crime and is taking payoffs and doesn’t have a liquor license.”18 Although police were eventually able to disperse the Stonewall bar crowd, the raid sparked riots spanning the next five days. These riots were one of the most prominent catalysts for intensifying the gay liberation movement, with Sargeant noting it “galvanized New York’s fearful gay men and lesbians into fighters.”15

“The poison was shame, and the antidote is pride.” – Craig Schoonmaker21

On November 2, 1969, Sargeant, his partner Craig Rodwell, Ellen Broidy, and Linda Rhodes proposed the first pride march to be held in New York City by way of a resolution at the Eastern Regional Conference of Homophile Organizations (ERCHO) meeting in Philadelphia8, 15, 19:

“That the Annual Reminder, in order to be more relevant, reach a greater number of people, and encompass the ideas and ideals of the larger struggle in which we are engaged—that of our fundamental human rights—be moved both in time and location.

We propose that a demonstration be held annually on the last Saturday in June in New York City to commemorate the 1969 spontaneous demonstrations on Christopher Street and this demonstration be called CHRISTOPHER STREET LIBERATION DAY. No dress or age regulations shall be made for this demonstration.

We also propose that we contact Homophile organizations throughout the country and suggest that they hold parallel demonstrations on that day. We propose a nationwide show of support.”2, 4

While the committee was brainstorming slogans for the march, “Gay Power” was thrown around but eventually discarded, as Craig Schoonmaker noted that gay individuals lacked real power to make change.8, 21 However, one thing they did have was pride. In a 2015 interview, Schoonmaker explained: “A lot of people were very repressed, they were conflicted internally, and didn’t know how to come out and be proud. That’s how the movement was most useful, because they thought, ‘Maybe I should be proud.’”21 The official chant for the march became “Say it clear, say it loud; gay is good, gay is proud.”5, 8, 15, 19, 21

Christopher Street Liberation Day on Sunday, June 28, 1970, marked the first anniversary of the Stonewall riots and was the first Gay Pride march in New York history.5 Additionally, over the same weekend, “the world’s first permitted parade advocating for gay rights” was staged on Hollywood Boulevard in Los Angeles and a “Gay In” was held in Golden Gate Park in San Francisco.1, 5, 8, 15, 19, 21 In time, events have expanded throughout the United States and the world as a whole. Pride is often celebrated at different times of the year elsewhere in the world, although many cities observe it in June.

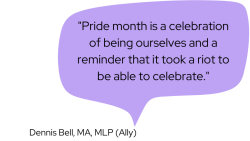

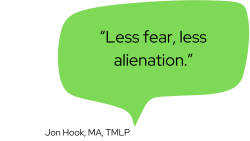

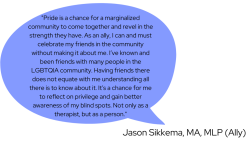

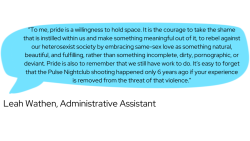

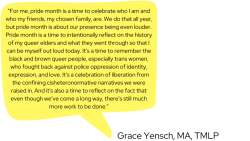

What does pride mean to you?

We asked our therapists and staff members what pride means to them, and this is what they had to say:

Mental wellness and pride go hand in hand. In fact, according to survey data from The Trevor Project, LGBT youth who had high levels of LGBT pride had nearly 20% lower odds of attempting suicide in the past year compared to those with lower levels of LGBT pride13. Supporting and cultivating pride in oneself and the greater LGBT community not only helps create change, but it also saves lives.

Every individual has the power to create positive change. We encourage you to take some time to reflect on this question – whether you are part of the LGBT community, or simply an ally. What can you do in your own life to work towards embracing your own understanding of pride and supporting that of others?

Written by Leah Wathen

References

- Cable News Network. (2021, October 31). LGBTQ Rights Milestones Fast Facts. CNN. Retrieved June 16, 2022, from https://www.cnn.com/2015/06/19/us/lgbt-rights-milestones-fast-facts/index.html

- Carter, D. (2004). Stonewall: The riots that sparked the Gay Revolution. St. Martin’s Press.

- Clements-Nolle, K., Marx, R., & Katz, M. (2006). Attempted suicide among transgender persons: The influence of gender-based discrimination and victimization. Journal of homosexuality, 51(3), 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v51n03_04

- Davenport, D. (2013, August 5). The Modern LGBT Community: Why We Celebrate Pride. LGBT+ Democrats of Virginia. Retrieved June 16, 2022, from https://lgbtvadem.org/blog/the-modern-lgbt-community-why-we-celebrate-pride/

- Fosburgh, L. (1970, June 29). Thousands of homosexuals hold a protest rally in Central Park. The New York Times. Retrieved June 16, 2022, from https://www.nytimes.com/1970/06/29/archives/thousands-of-homosexuals-hold-a-protest-rally-in-central-park.html

- Haas, Ann & Rodgers, Phillip & Herman, Jody. (2014). Suicide Attempts Among Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Adults: Finding of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. 10.13140/RG.2.1.4639.4641.

- Holland, B. (2017, June 22). How the mob helped establish NYC’s Gay Bar scene. History.com. Retrieved June 16, 2022, from https://www.history.com/news/how-the-mob-helped-establish-nycs-gay-bar-scene

- Holland, B. (2017, June 9). How activists plotted the first gay pride parades. History.com. Retrieved June 16, 2022, from https://history.com/news/how-activists-plotted-the-first-gay-pride-parades

- Hottes, Bogaert, Rhodes, Brennan, & Gesink. (2016). Lifetime Prevalence of Suicide Attempts Among Sexual Minority Adults by Study Sampling Strategies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, American Journal of Public Health, 106 (5), e1-e12. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303088

- MacInnes D. L. (2006). Self-esteem and self-acceptance: an examination into their relationship and their effect on psychological health. Journal of psychiatric and mental health nursing, 13(5), 483–489. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2006.00959.x

- Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Pride. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved June 16, 2022, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/pride

- Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Shame. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved June 16, 2022, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/shame

- Pride among LGBTQ youth. The Trevor Project. (2022, February 14). Retrieved June 21, 2022, from https://www.thetrevorproject.org/research-briefs/pride-among-lgbtq-youth/

- Robertson, J. D. (2017, June 7). Remembering Stormé – The Woman Of Color Who Incited The Stonewall Revolution. HuffPost. Retrieved June 16, 2022, from https://www.huffpost.com/entry/remembering-storm%C3%A9-the-woman-who-incited-the-stonewall_b_5933c061e4b062a6ac0ad09e

- Sargeant, F. (2010, June 22). 1970: A first-person account of the first Gay Pride March. The Village Voice. Retrieved June 16, 2022, from https://www.villagevoice.com/2010/06/22/1970-a-first-person-account-of-the-first-gay-pride-march/

- Sibilla, N. (2015, June 28). How Liquor Licenses Sparked the Stonewall Riots. Reason.com. Retrieved June 16, 2022, from https://reason.com/2015/06/28/how-liquor-licenses-sparked-stonewall/

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2016). Sexual Orientation and Estimates of Adult Substance Use and Mental Health: Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-SexualOrientation-2015/NSDUH-SexualOrientation-2015/NSDUH-SexualOrientation-2015.htm

- Thomas, J. (2011, June 27). The Gay Bar: Why the Gay Rights Movement was born in one. Slate Magazine. Retrieved June 16, 2022, from http://www.slate.com/articles/life/the_gay_bar/2011/06/the_gay_bar_4.html

- Wallenfeldt, J. (2022, May 27). Why is pride month celebrated in June? Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved June 16, 2022, from https://www.britannica.com/story/why-is-pride-month-celebrated-in-june

- Wanta, Niforatos, Durbak, Viguera, & Altinay (2019). Mental Health Diagnoses Among Transgender Patients in the Clinical Setting: An All-Payer Electronic Health Record Study. Transgender Health, 4(1), 313-315. http://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2019.0029

- Zaltzman, H. (2016, June 14). Allusionist 12: Pride – transcript. The Allusionist. Retrieved June 16, 2022, from https://www.theallusionist.org/transcripts/pride