Autism in Women and Girls

What do you picture when you think of an individual with autism? Do you see a minimally-verbal little boy who is obsessed with trains and flaps his hands? What about a young man like Sheldon Cooper from The Big Bang Theory, or a savant like in the movie Rain Man? Were any of your images of a girl or woman? Probably not.

There is a general assumption that autism is a male condition. In fact, using semi-structured interviews, Watson (2014) found that parents frequently perceived autism to be a “boy’s disorder.” Research, and therefore the subsequent diagnostic criteria that has emerged, has been primarily based on male subjects (Kirkovski et al., 2013). Autism is more frequently diagnosed in boys, with a ratio of 4:1 (Barnard-Brak, Richman, & Almeksdash, 2019), and boys are referred for a diagnostic assessment 10 times more often than girls (Wilkinson, 2008). Women and girls also tend to receive autism diagnoses at a later age on average than boys (Kirkovski et al., 2013; Zener, 2019). However, emerging research suggests that autistic women and girls show different traits than boys and men with autism. Without updates to diagnostic screening tools and professional education, a significant underdiagnosis of females with autism likely has and will continue to occur.

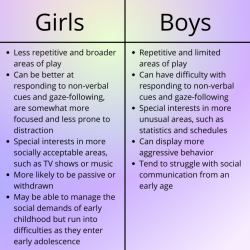

Basic differences in behavior between autistic boys and girls

Misdiagnosis and Late diagnosis

Despite the growing evidence suggesting a profile of autism unique to females, education has not been widespread. As professionals often do not have sufficient awareness or knowledge on autism in females, they may not consider it as the underlying cause of mental health difficulties. Women and girls are statistically more likely to be diagnosed – as well as misdiagnosed – with other conditions such as depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorders, personality disorders, eating disorders, or others before they are diagnosed with autism (Au-Yeung et al., 2019; Lockwood et al., 2021). This is not only due to the likelihood of co-occurring conditions but also due to the stereotypical model of autism that has been popularized within society.

Various autistic characteristics, such as flat affect, social withdrawal, or disordered eating behaviors, are often confused with symptoms of mental illness; or, conversely, mental health difficulties are often perceived to be the result of autism rather than due to independent conditions (Au-Yeung et al., 2019). There are also numerous clinical barriers to proper diagnosis including clinicians’ lack of education and understanding of autism, lack of communication between clinician and client, focus on medication, and focus on treating surface symptoms rather than addressing the root cause of the behavior (Au-Yeung et al., 2019).

Common pathways for women to receive an autism diagnosis include having a family member or partner diagnosed with autism and subsequently identifying signs in themselves, recognizing personal traits in accounts by autistic women, or exploring the possibility of autism after experiencing employment difficulties or burnout. Women may be more negatively affected by the time they reach adolescence and adulthood, due to the mental strain of encountering difficulties without the awareness that those difficulties may be related to autism (Zener, 2019).

Autism in women and girls can present in unexpected ways. Symptoms such as disordered eating, anxiety, depression, and difficulty with emotion regulation may actually be more surface-level behaviors better represented by a diagnosis of autism. For example, anxiety may be primarily due to difficulty with change, depression due to the stress of coping in a world that’s not designed with the needs of individuals wtih autism in mind, and food restriction due to sensory difficulties or difficulties identifying internal signals such as hunger. Screening and diagnostics often lack the ability to pick up on autistic traits in women and girls, as they have been created using predominately male samples (Lai et al., 2017; Carpenter et al., 2019). Unless practitioners are willing to dig deeper, the root cause of a client’s struggles may never be properly identified, leading to improper treatment, confusion, and frustration.

Diagnostic differences

Common autistic traits seen in females with autism are often different and more subtle than in males. Boys with autism are more prone to isolation, restrictive interests, and repetitive behaviors (Hiller et al., 2014). Conversely, females with autism tend to have higher levels of social motivation than males (Hiller et al., 2014; Stark 2019). While it can be obvious when a boy with autism is struggling socially early on, girls’ social difficulties tend to become more noticeable and pronounced over time, as the social landscape becomes more difficult to navigate (Mandy et al., 2018). Additionally, girls with autism tend to internalize their feelings rather than externalize them (Hiller et al., 2014; Mandy et al 2012) and may experience increased sensory processing issues (Lai et al., 2011). Even with comparable levels of autistic traits, females require more difficulties than males to receive an autism diagnosis, such as minimal speech or pronounced behavioral issues (Duvekot et al., 2017; Geelhand et al., 2019). The special interests of girls with autism also tend to be more “socially appropriate” and potentially focus on characters or animals rather than objects (e.g., Disney princesses, horses, book series, bands) (Nowell et al., 2019; Saporito, 2022) while the stereotype is that boys with autism are into trains.

Masking

In addition to differences in behavioral presentation, women and girls are more likely to engage in masking behaviors. Masking refers to the act of concealing autistic traits to pass as neurotypical. Often utilized to reduce barriers in other aspects of their lives, masking can include suppressing stims (short for self-stimulatory behaviors), forcing eye contact or speech, creating and memorizing scripts for social interactions, mirroring the behavior of others, and more. These behaviors can happen consciously or unconsciously, making them difficult to recognize. Because of this, women and girls with autism may slide by relatively unnoticed until social demands increase (Lockwood et al., 2021).

Research has found that being female was a significant predictor of complex imitation skills (Hiller et al., 2014). From a distance, the social challenges of girls with autism are concealed; however, they do not appear to be hidden from peers (Dean et al., 2017). Whereas boys with autism tend to be overtly rejected by their peers, girls with autism are neither accepted nor rejected; instead, they appeared to be overlooked (Dean et al., 2014). This masking behavior may contribute to school staff members’ failure to recognize when an undiagnosed girl with autism is struggling. While masking may help women with autism to fit in, it has been described as physically and mentally exhausting and is associated with increased suicide risk (Cassidy et al., 2019). It also may damage females’ sense of self and identity, as they may feel unsure of who they really are. Because it often occurs unconsciously, masking can also be a significant barrier to receiving diagnosis and much-needed support.

Proper diagnosis matters

Failure to consider autism as a primary cause consequently leads to undertreatment or inappropriate treatment. Undiagnosed girls have fewer opportunities to learn critical safety, social, and adaptive skills – skills that are particularly important for women. Due to their literal way of thinking and struggles reading social cues, women with autism are more susceptible to manipulation and sexual abuse (Milner et al., 2019). Growing up undiagnosed can be scary, confusing, frustrating, and isolating. Thankfully, research into autism in females has increased over the years, and the internet has provided access to community and resources that were previously unattainable. We still have much to learn, but as our understanding and awareness continues to grow, there is hope that women and girls with autism will have equal access to diagnosis and support to help them live happy, healthy, self-confident, and fulfilling lives.

Written by Leah Wathen

References

Au-Yeung, S. K., Bradley, L., Robertson, A. E., Shaw, R., Baron-Cohen, S., & Cassidy, S.

(2019). Experience of mental health diagnosis and perceived misdiagnosis in autistic, possibly autistic and non-autistic adults. Autism, 23(6), 1508–1518. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318818167

Barnard-Brak, L., Richman, D. & Almekdash, M.H. (2019). How many girls are we missing in ASD? An examination from a clinic- and community-based sample. Advances in Autism, 5(3), 214-224. https://doi.org/10.1108/AIA-11-2018-0048

Carpenter, B., Happe, F., & Egerton, J. (2019). Girls and Autism: Educational, Family and

Personal Perspectives.

Cassidy, S. A., Gould, K., Townsend, E., Pelton, M., Robertson, A. E., & Rodgers, J. (2020). Is

Camouflaging Autistic Traits Associated with Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviours? Expanding the Interpersonal Psychological Theory of Suicide in an Undergraduate Student Sample. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 50(10), 3638–3648. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04323-3

Dean, M., Kasari, C., Shih, W., Frankel, F., Whitney, R., Landa, R., Lord, C., Orlich, F., King,

B., & Harwood, R. (2014). The peer relationships of girls with ASD at school: comparison to boys and girls with and without ASD. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines, 55(11), 1218–1225. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12242

Dean, M., Harwood, R., & Kasari, C. (2017). The art of camouflage: gender differences in the

social behaviours of girls and boys with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 21(6), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361316671845

Digitale, E. (2015, Sept 3). Girls and boys with autism differ in behavior, brain structure.

Stanford Medicine News Center. https://med.stanford.edu/news/all-news/2015/09/girls-and-boys-with-autism-differ-in-behavior-brain-structure.html

Driver, B. & Chester, V. (2021). The presentation, recognition and diagnosis of autism in

women and girls. Advances in Autism, 7(3), 194-207. https://doi.org/10.1108/AIA-12-2019-0050

Duvekot, J., van der Ende, J., Verhulst, F. C., Slappendel, G., van Daalen, E., Maras, A., &

Greaves-Lord, K. (2017). Factors influencing the probability of a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder in girls versus boys. Autism: the international journal of research and practice, 21(6), 646–658. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361316672178

Geelhand, P., Bernard, P., Klein, O., van Tiel, B., & Kissine, M. (2019). The role of gender in

the perception of autism symptom severity and future behavioral development. Molecular autism, 10, 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-019-0266-4

Hiller, R. M., Young, R. L., & Weber, N. (2014). Sex differences in autism spectrum disorder

based on DSM-5 criteria: evidence from clinician and teacher reporting. Journal of abnormal child psychology, 42(8), 1381–1393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-014-9881-x

Hull, L., Petrides, K.V., & Mandy, W. (2020). The Female Autism Phenotype and

Camouflaging: A Narrative Review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 7, 306-317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-020-00197-9

Iris (2018, Nov 12). What Women With Autism Want You to Know [Video]. YouTube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NwEH9Ui4HV8

Kirkovski, M., Enticott, P. G., & Fitzgerald, P. B. (2013). A review of the role of female gender

in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 43(11), 2584–2603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-1811-1

Lai, M. C., Lombardo, M. V., Ruigrok, A. N., Chakrabarti, B., Auyeung, B., Szatmari, P.,

Happé, F., Baron-Cohen, S., & MRC AIMS Consortium (2017). Quantifying and exploring camouflaging in men and women with autism. Autism: the international journal of research and practice, 21(6), 690–702. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361316671012

Lockwood Estrin, G., Miller, V., Spain, D., Happe, F., & Colvert, E. (2021). Barriers to Autism

Spectrum Disorder Diagnosis for Young Women and Girls: A Systematic Review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 8, 454-470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-020-00225-8

Mandy, W., Chilvers, R., Chowdhury, U., Salter, G., Seigal, A., & Skuse, D. (2012). Sex

differences in autism spectrum disorder: evidence from a large sample of children and adolescents. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 42(7), 1304–1313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1356-0

Mandy, W., Pellicano, L., St Pourcain, B., Skuse, D. & Heron, J. (2018). The development of

autistic social traits across childhood and adolescence in males and females. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 59, 1143-1151. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12913

Milner, V., McIntosh, H., Colvert, E., & Happé, F. (2019). A Qualitative Exploration of the

Female Experience of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 49(6), 2389–2402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-03906-4

Nowell, S.W., Jones, D.R. & Harrop, C. (2019). Circumscribed interests in

autism: are there sex differences? Advances in Autism, 5(3), 187-198. https://doi.org/10.1108/AIA-09-2018-0032

Saporito, K. (2022, February 3). Autism Is Underdiagnosed in Girls and Women. Psychology

Stark, E. (2020). Autism in women. Psychologist, 32(8), 38–41.

Watson, L. E. (2014). “Living life in the moment”: chronic stress and coping among families of high-functioning adolescent girls with autism spectrum disorder (Doctoral dissertation, Boston College).

Wilkinson, L. A. (2008). Self-Management for Children With High-Functioning Autism

Spectrum Disorders. Intervention in School and Clinic, 43(3), 150–157.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1053451207311613

Zener, D. (2019), “Journey to diagnosis for women with autism”, Advances in Autism, 5(1), 2-